Stop Chasing Consensus. Start Building on Predictions.

I came across Jensen Huang's talk on AI and computing's future a few weeks ago. As time is my scarcest commodity, like all videos, I ran it through my pareto prompt: "Extract the 20% of insights that deliver 80% of the value."

The AI's summary was insightful, but one line stood out, not for what it said, but for the deeper method it revealed: "Jensen's edge comes from inverting questions from first-principles decomposition." This wasn't just a summary of his success; it was a blueprint for thinking in an age where knowledge is abundant. Jensen didn't build NVIDIA by following consensus (Moore's law)—he built it by predicting what would survive when the foundation everyone relied on broke.

When AI can deliver PhD-level answers to almost any question, the advantage no longer comes from just knowing more but rather from intuition at the edges of prevailing knowledge— by asking different questions. This is the method Jensen has mastered, and it's the discipline that will survive long after machines compress all documented knowledge into instant, accessible synthesis.

First Principles to Question Inversion

Musk popularized first-principles thinking—his ability to understand domains like space travel by decomposing them to foundational truths. Jensen's method inverts this. He takes first-principles decomposition and flips the question to spot what comes next.

The approach breaks into three steps. First, decompose to foundations. Ask: What does X depend on? Not what X does or how it works, but what fundamental constraint or enabler makes X possible in the first place.

Second, identify where this foundation breaks. Every dependency has limits—physical, economic, structural. Find the constraint that will eventually fold. This isn't speculation. It's reading the original papers, understanding the physics or economics, and spotting the point where current success becomes future failure.

Third, invert the question. Instead of asking what's possible now, ask what survives when the current foundation fails. This is where insight lives. While most people are busy optimizing for today's reality, the true visionaries are positioning themselves for what comes after the current paradigm breaks.

This isn't just analysis. It's a discipline for generating insight that doesn't exist in the corpus yet. Consider this example: In 1993, everyone asked:

"What can CPUs do?" Jensen asked "What do CPUs depend on, and what happens when that dependency fails?" The first question led to incremental improvements. The second led to GPUs.

The method matters now more than ever because we're living through a fundamental shift in how computing works—a shift that makes the old models of expertise obsolete.

The Observable Shift: Computing Goes 100% Generative

Classical computing was storage-based. You saved files, retrieved them, consumed them. The entire architecture revolved around making retrieval faster and storage cheaper. AI computing operates differently. It's generation-based: context comes in, processing happens in real-time, output gets produced on demand. The demand just shifted towards GPUs.

This shift is irreversible for three reasons. First, AI cannot be pre-compiled. You can't package all possible responses ahead of time because the input space is infinite. The system must process context in real-time to generate relevant responses. Second, the marginal cost of generation trends toward zero. Once the model is trained, producing another answer costs almost nothing. Third, bespoke intelligence beats generic answers. A response tailored to your exact context and constraints is worth more than a cached reply designed for the average case.

The result: computing transforms from a retrieval system into a dynamic synthesizing engine. Instead of storing answers, we store the capacity to generate them.

Future computing systems will respond to different forms of user interface. The one I favor is speaking to my computer. Whisper works so well that most of my input that once was keyboard and mouse based has moved to voice—something Siri promised but never delivered. I don't want to click through hundreds of screens or stare at bar charts designed to convince me of something. I want answers to specific questions in context.

With tools like Cursor and Claude Code, I can use the voice option to speak my software requirements and get code that comes close to my expectations in hours—work that would take weeks or months otherwise. We aren't going back to storage-based retrieval. The future is generative.

This irreversible shift to generative computing is not just a technical change; it's a fundamental change in the value of knowledge itself. Which brings us to the current state of AI capabilities—and why traditional notions of expertise are becoming obsolete.

PhD-Level Knowledge Is Already Here

Claude Sonnet, ChatGPT, Gemini—each release compresses more expertise into systems you can access right now. These aren't prototypes or future promises. They're production tools doing PhD-level work today.

Ask Claude to revise 10,000 lines of code across hundreds of files, fix bugs, and add features. It does it. That's PhD-level software engineering execution, not just syntax checking. Ask it to derive and apply the Black-Scholes formula with parameter sensitivity analysis. It handles the math and the interpretation. That's PhD-level quantitative finance. Ask it to design and optimize neural network architectures for specific domains. It reasons through the trade-offs and proposes solutions. That's PhD-level machine learning engineering.

This isn't coming. It's here. Knowledge abundance is the new baseline. Every domain where expertise can be codified into patterns and principles now has those patterns available on demand, instantly, for near free.

But here's what matters: execution capability is not the same as intuition about when to use it, what can go wrong, or why it matters. AI can revise your codebase, but it doesn't know if the refactor makes the system more fragile. It can design architectures, but it doesn't know if you're solving the right problem.

The gap between execution and judgment is where human value now lives.

What AI Gives You: Knowledge at Scale, Custom to Your Context

Knowledge, in the classical sense, is facts, data, published research, peer-reviewed findings—the public corpus. AI compresses this at superhuman scale. It's trained on everything written, cited, and documented. Ask it about semiconductor physics, and it synthesizes decades of research. Ask it about macroeconomic theory, and it draws from hundreds of papers and textbooks.

But AI doesn't stop at public knowledge. It can integrate your private content. Company documents, proprietary processes, internal datasets, personal notes—all of it can become part of the context. You can feed your custom corpus into the system: strategic frameworks, unique methodologies, domain-specific insights that don't exist in any public training data. The result is PhD-level public knowledge combined with your proprietary knowledge, creating bespoke intelligence synthesis.

The machine now has access to both consensus knowledge and your specialized edge. It can reason about your business using frameworks only you and your team understand. It can analyze your data through lenses that reflect your unique constraints and opportunities.

But here's the boundary: knowledge is not understanding. Understanding is not wisdom. And neither can be prompted into existence.

You Cannot Prompt Your Way to Intuition

Understanding means knowing what matters in a specific context. Wisdom involves applying knowledge with discernment, ethics, and long-term perspective—especially in complex or uncertain contexts. Intuition is fast, subconscious judgment derived from internalized knowledge and pattern recognition, often without deliberate reasoning.

AI can execute at PhD-level. It can revise code, apply models, design systems. But intuition isn't about execution speed. It's about judgment forged through friction.

The Dreyfus Model of skill acquisition shows this clearly. You move through five stages: Novice, Advanced Beginner, Competent, Proficient, Expert. Each stage builds on the previous through deliberate practice, pattern recognition from experience, and learning from failures. AI shortcuts give you the answer but skip the stages that build intuition and judgment.

You don't learn to recognize when something's wrong if you never debug it yourself. You don't develop instinct for what will break if you never live with the consequences of brittle design. You don't build taste for elegant solutions if you never had to maintain ugly ones.

The danger of these powerful tools is that they can create an illusion of competence. Research highlights this starkly: students using ChatGPT to solve problems worked faster, but their learning was superficial, leading to failure on follow-up tests. In contrast, those who struggled with the material using traditional search methods retained the knowledge and performed better in the long run. The lesson is clear: the struggle is not an obstacle to learning; it is the learning.

Tools like Obsidian, especially LYT workshops, have helped me think and separate my thoughts from prompt-generated content. Mindmap with Excalidraw is another powerful tool in this ability to visualize—connect information, work with knowledge to develop understanding and intuition that can't be downloaded without effort.

The human edge lives where AI's training fundamentally limits it. This is not about what AI can't do today, but what it structurally cannot learn from its training approach.

The Human Edge: Where AI Falls Short

When you ask AI a question, you're not getting neutral synthesis. You're getting consensus, filtered through alignment, shaped by the training process. AI is a pattern-matching engine trained on what people wrote, cited, and published. This creates three fundamental gaps that only humans can fill.

1) Seeing Beyond Consensus

AI defaults to the most common answer—not because it doesn't know better, but because it was trained to suppress alternatives. During alignment, human raters systematically rewarded familiar, conventional responses. Over millions of examples, this taught the model to hide edge cases, unconventional scenarios, and low-probability failures.

The problem: your AI knows about edge cases. It just won't tell you unless you ask differently.

The solution is a technique called Verbalized Sampling, developed by Stanford researchers. Instead of accepting single answers, you request distributions. Instead of asking "What could go wrong with this strategy?" you ask "Generate five failure scenarios with probabilities, ranging from common high-probability cases to rare edge cases."

This simple reframing forces the model to surface the full spectrum—not just the typical failure everyone expects, but the tail-risk scenarios hidden in its training data. The result: you access 1.6 to 2.1 times more diverse scenarios, including the edge cases that matter most for robust decision-making.

Real insight lives where consensus ends. Verbalized Sampling shows you what's been trained away. But even with the right prompts, you still need the intuition to recognize which edge cases actually matter. That intuition comes from experience—from seeing or causing failures before and learning to spot the warning signs.

This same limitation extends to challenging accepted beliefs. Consensus in the corpus doesn't mean truth. It means agreement among those who published. Many accepted beliefs are artifacts of incentives, measurement bias, or incomplete data.

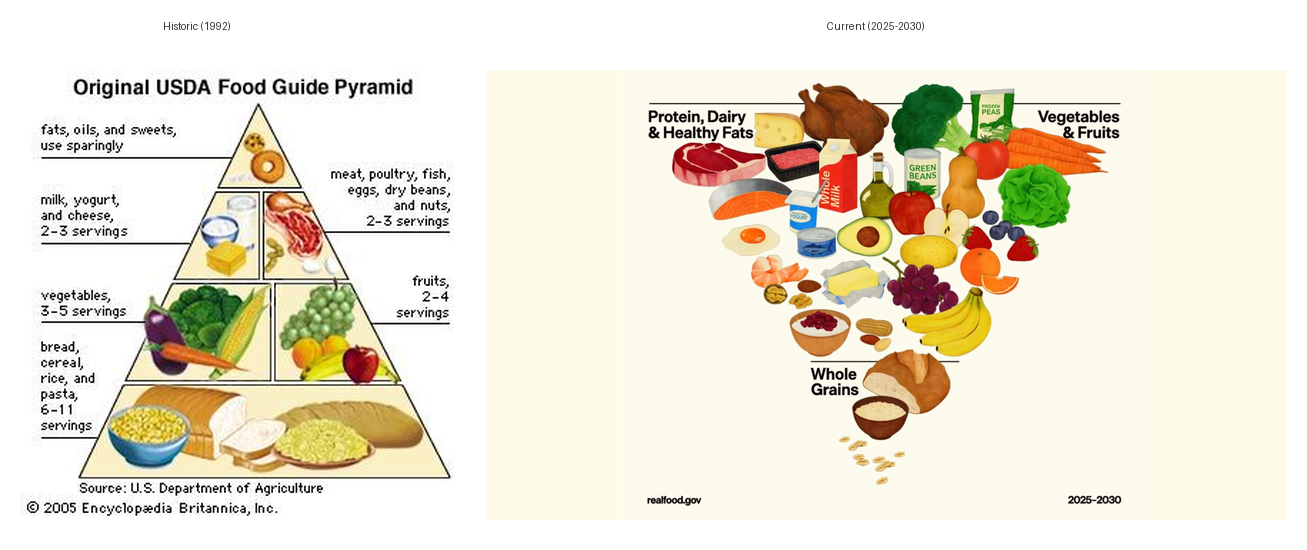

Consider the obesity crisis in the United States and how nutritional guidance evolved—or failed to evolve—alongside it. The 1992 USDA food pyramid championed a diet rich in grains, placing them at its base. During the decades this guidance dominated, obesity rates climbed from 23% in 1988-1994 to over 42% by 2017-2020. The correlation was undeniable, yet the guidance persisted.

The pyramid's logic was built on flawed causation: dietary fat was blamed for obesity and heart disease, so the solution was to replace fat with carbohydrates—specifically grains and starches. The food industry responded by creating "low-fat" processed foods loaded with sugar and refined carbohydrates. What followed wasn't health improvement but metabolic catastrophe: rising diabetes, heart disease, and chronic inflammation.

Only recently has the Kennedy administration's 2025-2030 dietary guidelines introduced an inverted food pyramid, prioritizing protein, healthy fats, and full-fat dairy at its widest top, with whole grains at the narrow bottom. This change reflects a major reset in nutrition policy, aiming to address the chronic disease epidemic by emphasizing whole, nutrient-dense foods over highly processed, grain-centric diets.

The original consensus persisted for decades—not because the evidence was strong, but because it aligned with institutional interests (agricultural lobbies, food manufacturers) and became too embedded to easily challenge. The obesity crisis was the constraint failure, visible in the data for years, that finally forced a reversal.

AI synthesizes current consensus. In 2026, it will confidently recommend the grain-heavy pyramid. Humans spot where consensus is a comfortable lie. The human edge is questioning the foundation of consensus claims: Why is this believed? Who benefits from this belief? What evidence would falsify it?

2) Reasoning from Causation, Not Correlation

AI is trained on correlations in the corpus. X and Y appear together often, so it learns to associate them. But correlation is not causation, and causation lives in constraint reasoning, not pattern matching.

The fundamental problem: while LLMs excel at spotting patterns, they struggle with true causal reasoning. Recent research tested whether state-of-the-art LLMs could distinguish between "these two things happen together" and "this thing causes that thing." The results were sobering—the models performed barely better than random guessing. They could tell you what correlates, but not what causes what.

The breakdown gets worse when the question is phrased differently than the training data. Change a few words or use different variable names, and the model's reasoning falls apart. This reveals the core limitation: AI relies on pattern matching, not genuine causal understanding.

The human edge is identifying why X and Y correlate, decomposing to the mechanism, and spotting when that mechanism breaks. This kind of causal reasoning requires intuition built from experience—knowing which mechanisms matter, which constraints bind first, and what the early warning signs look like.

3) Predicting the Breaks

This brings us full circle to Jensen's method. AI can tell you what happened when constraints bound in the past. It can synthesize historical patterns and outcomes. But it cannot predict what happens when different constraints bind in the future—because those scenarios don't exist in the training data yet.

Prediction requires understanding causation, not just correlation. It requires decomposing systems to their fundamental dependencies, identifying which constraints will bind next, and reasoning about what survives when they do. This is constraint-based reasoning, and it operates outside the training distribution by definition.

The human edge is asking: Given where I am, what breaks next for me? This requires reasoning from your unique position—your constraints, your context, your skin in the game. AI has no position. It averages across all positions. Wisdom lives in marginal thought.

The Discipline That Survives: Hypothesize, Predict, Falsify

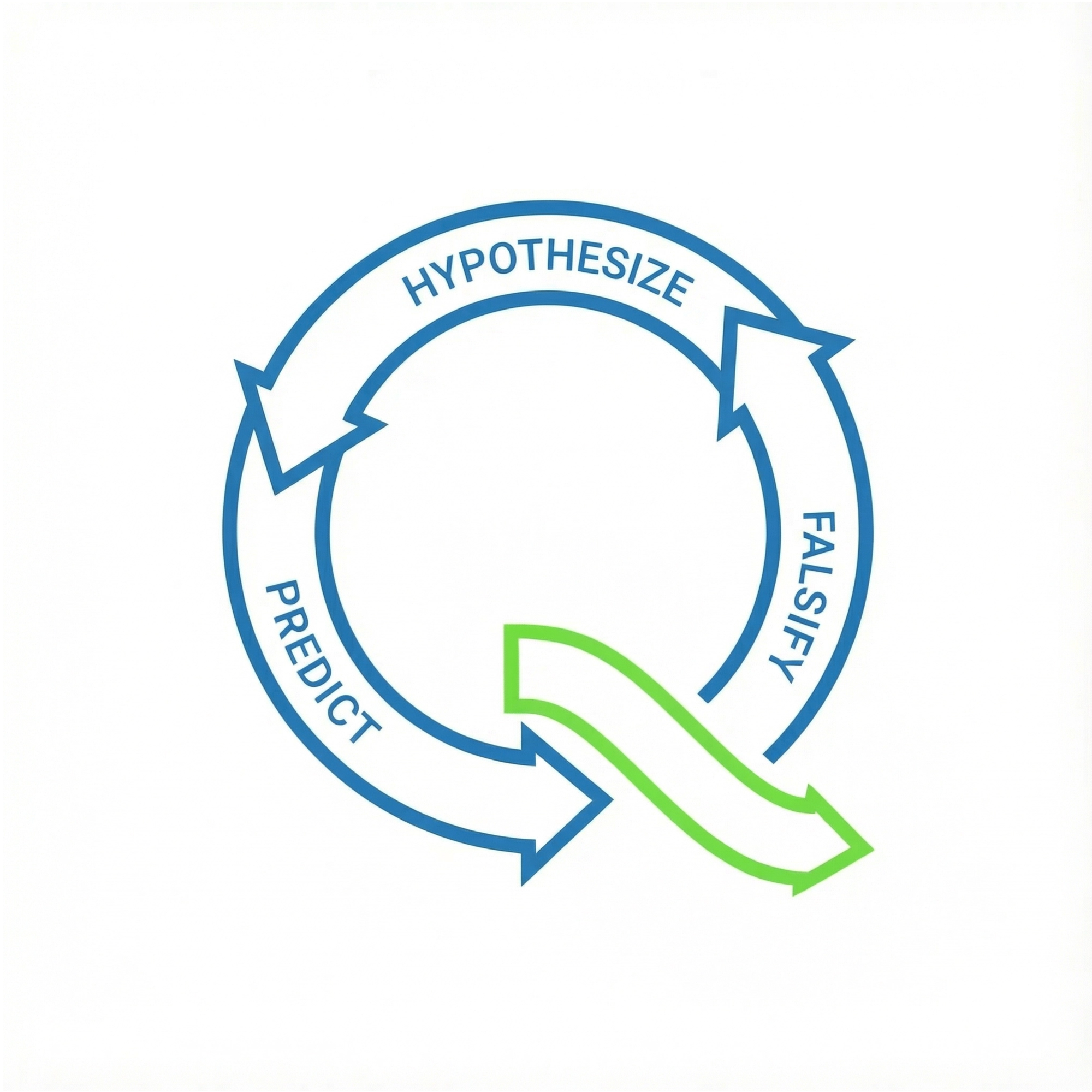

You can't passively absorb your way to original insight anymore. When knowledge is abundant and AI can synthesize it instantly, the edge shifts to active method. The most useful framework I've encountered for this came from a course by Superlinear, who taught the scientific method through Robert Pirsig's "Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance." The structure is simple but demanding in practice.

State the problem. Hypothesize the cause. Design experiments to test each hypothesis. Predict the results. Observe what actually happens. Conclude, then loop back—hypothesize, predict, falsify or verify. This isn't brainstorming or speculation. It's a process of structured falsification, where the goal is not to prove yourself right, but to rigorously test your ideas to see where they break.

The reason this matters: among the noise, there are very few signals. Among the signals, there are few things that are actually important. And among the important signals, there are few things that are likely. Making predictions is about forming your own view on signal, importance, and likelihood. It forces you to identify what current success depends on, trace that dependency to its foundational constraint, predict when the constraint binds, and reason about what survives when it breaks.

Then you test the prediction against reality, looking for evidence that proves you wrong. What remains after this process are convictions forged by hindsight and aimed at foresight. These aren't opinions or hunches. They're beliefs that have survived deliberate attempts at falsification.

Turning predictions into reality requires three things: internalizing the constraint logic until it becomes intuition, having strong convictions built from that internalized understanding, and knowing how to build or position for what comes next. But the foundation is always the same—seek extreme clarity, practice intellectual honesty, and detach from being right. You've got to be able to falsify and validate without ego getting in the way.

This method operates outside the training distribution. AI can't replicate it because the corpus contains what happened. This method predicts what happens next.

The Parallel: Polya's Problem-Solving as Structured Falsification

This approach isn't new. George Polya formalized it in 1945 with "How to Solve It," a book on mathematical problem-solving that became a classic because the method works across domains. Last year, Jeremy Howard from Fast.AI released solve it, a modern implementation of the same framework. The core structure remains consistent across decades because the underlying principle is sound.

Polya's four steps mirror Hypothesis-Predict-Falsify almost exactly. First, understand the problem. This isn't about restating the question. It's about defining the hypothesis space: What are we actually asking? What assumptions are embedded in the question itself?

Second, devise a plan. Generate testable sub-hypotheses. Ask: How would we know if we're wrong? What evidence would falsify this approach? Third, execute with verification. Don't build the entire solution and hope it works. Falsify incrementally at minimum scale. Test the weakest link first. If it breaks there, you've saved time. If it holds, move to the next weakest point.

Fourth, reflect. Extract transferable knowledge and identify blind spots. Ask: What did we learn about the method itself, not just the solution? This step is what builds intuition over time. Each cycle through the process refines your judgment about which approaches fail and why.

Polya taught problem-solving as disciplined falsification, not solution-finding. The goal wasn't to arrive at an answer quickly. It was to develop judgment about which approaches fail and why. Same principle applies now: the method for generating answers matters more than the answers themselves.

Why Contrarian Thinking Becomes More Valuable, Not Less

Generative AI trains on consensus. By definition, the training corpus is what people wrote, cited, and published. The model learns the center of the distribution because that's where most of the data lives. As AI gets better at synthesis, it gets better at producing consensus answers faster and more fluently.

This makes contrarian insight more valuable, not less. Contrarian thinking lives outside the distribution. It's pre-consensus by definition. It emerges from reasoning that hasn't been documented yet because the constraint it predicts hasn't broken yet. AI can't commoditize this because it doesn't exist in the training data.

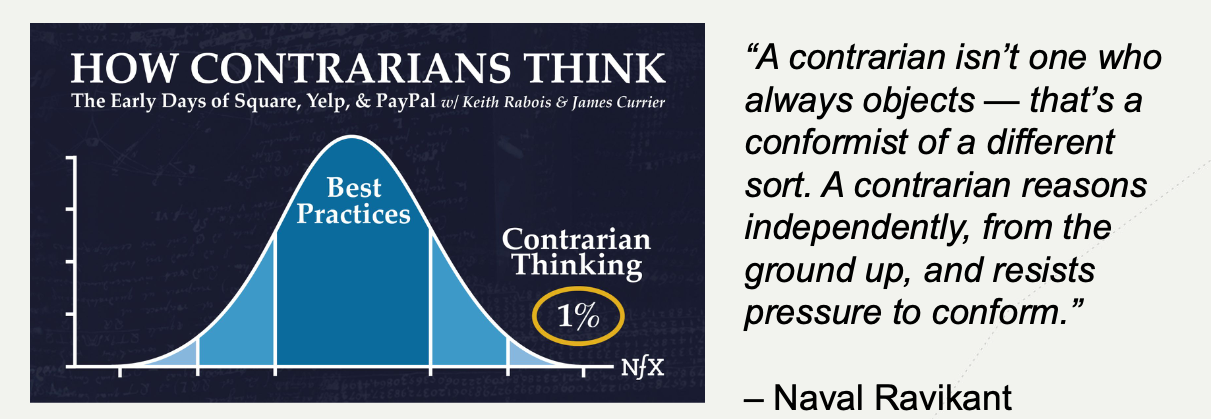

But contrarian doesn't mean disagreement for its own sake. It doesn't mean reflexive skepticism or taking the opposite position just to be different. As Naval Ravikant said: "A contrarian isn't one who always objects—that's a conformist of a different sort. A contrarian reasons independently, from the ground up, and resists pressure to conform."

Contrarian means independent reasoning from constraints, not from citations. It means decomposing to foundations, identifying where those foundations fail, and predicting what survives the failure—regardless of what consensus currently believes.

As AI gets better at synthesizing what's known, the premium shifts entirely to predicting what's next. The value gap between "retrieve consensus" and "reason from constraints" widens. And because constraint-based reasoning requires the kind of intuition we've been discussing—pattern recognition from experience, judgment about which mechanisms matter, instinct for when consensus is wrong—it becomes the only durable edge in a world where knowledge is free.

Putting Constraint-Based Reasoning into Practice

So how does this apply if you're not making a 15-year bet on semiconductor physics? The method scales down from trillion-dollar decisions to daily professional choices. The discipline is the same—only the stakes and timescales change.

For the Project Manager: You're managing a complex software delivery with multiple dependencies. The default question is "How can we deliver this project on time?" This optimizes for today's constraints. The constraint-based question is "What is the single biggest dependency that, if it fails, will derail this entire project? And what is our plan for when it does?"

This inversion shifts focus from execution velocity to fragility analysis from experience. You decompose the project to its critical path, identify the constraint most likely to bind (vendor delay, key personnel, technical blocker), predict when it breaks, and position alternatives before the break happens. This is the same method Jensen used—just applied to a 6-month project instead of a 15-year industry shift.

For the Marketer: You're running a campaign to drive conversions. The pattern-matching question is "How can we get more clicks on this ad?" The constraint-based question is "What is the underlying customer motivation that drives conversion, and what evidence would prove our assumption about that motivation is wrong?"

This moves from correlation (clicks) to causation (motivation). You hypothesize what constraint the customer faces (time scarcity, decision paralysis, trust deficit), predict how they'll respond to different messaging that addresses each constraint, run experiments to falsify weak hypotheses, and build your strategy around the causal mechanism that survives testing. The corpus gives you what worked for others. Constraint reasoning tells you what will work for your specific customer in their specific context.

For the Developer: You receive a feature request to add complex filtering to a data table. The execution question is "How do I build this feature?" The constraint-based question is "What is the foundational problem this feature is trying to solve, and is there a simpler way to solve it that avoids the complexity of the current request?"

You decompose to first principles: the user wants to find specific data faster. The proposed solution is complex filters. But the constraint might be that users don't know what they're looking for until they see it. In that case, better search or intelligent defaults might solve the root problem without the complexity. You predict which approach reduces user friction more, build minimum viable tests of each, let reality falsify weak options, and implement what survives.

The pattern across all three: decompose to constraints, predict when they bind, invert the question from "how do I optimize for today" to "what survives when this breaks." The scale changes. The method doesn't.

To make this method a consistent discipline, I've found it helpful to integrate it into my daily Obsidian workflow. I use Obsidian to capture these decompositions. When I face a decision, I create a note asking:

- First Light: What is on my mind? What is my focus today?

- Decisions:

- What actually happened vs. what I predicted? Where is my causal understanding wrong?

- What does this action depend on? Where does it break? What survives?

- Last Light: What are my wins today? What's on tap for tomorrow?

Freewrite

This isn't just note-taking. It's building the pattern recognition that becomes intuition. Each cycle—decompose, predict, test, reflect—trains my judgment about which constraints matter and which breaks to position for. The tools don't give you the answers. They structure the thinking that develops the judgment to know which questions will lead to answers that matter.

Jensen's Proof: GPU Prediction from Constraint Decomposition

In 1993, everyone was betting on CPUs. Moore's Law was delivering, serial processing speeds were doubling every 18 months, and the entire industry was optimizing for single-threaded performance. The consensus was clear: CPUs were the future.

Jensen Huang decomposed to foundations. He asked: What does CPU performance depend on? The answer was Dennard scaling, a principle from semiconductor physics that said you could shrink transistors, increase clock speed, and keep power density constant. This was the engine behind Moore's Law gains.

Then he read the foundation papers. Dennard scaling depends on voltage scaling. As transistors shrink, you reduce the voltage proportionally, which keeps power consumption manageable while allowing higher clock speeds. But Jensen spotted the constraint: voltage can't scale past quantum tunneling effects. This is a physics limit, not an engineering challenge. Around 2005, transistors would get small enough that electrons would start jumping barriers they shouldn't. Voltage scaling would stop.

He inverted the question. Instead of asking what CPUs could do, he asked: What survives when serial speed plateaus? When you can't make individual threads go faster, what performance path remains? The answer was parallelism. You still get more transistors per chip as lithography improves, but you can't run them faster. You can only run more of them simultaneously.

This led to the GPU architecture bet. Instead of a few complex cores optimized for serial speed, build thousands of simple cores optimized for parallel throughput. This was a 15-year early bet—made in 1993 for a constraint that wouldn't bind until around 2007-2008. And it wasn't in the consensus. The consensus said CPUs would keep scaling. Jensen's constraint analysis said parallelism wins when serial scaling dies.

The result: NVIDIA became a trillion-dollar company by positioning for what survives when the foundation breaks. This wasn't lucky timing or visionary genius in the mystical sense. It was method. Decompose to constraints, predict when they bind, invert to what survives. The discipline produced the insight. The insight produced the conviction. The conviction guided the decision 15 years before the market validated it.

The New Frontier: Humanity's Next Level of Understanding

We now have generative intelligence that compresses all documented knowledge at PhD-level. We have methods to pull edge cases from distributions that would otherwise give us only consensus. We have discipline for constraint-based reasoning and falsification. The infrastructure is in place.

But the frontier isn't more knowledge. We have enough knowledge. The frontier is new connections only humans can make.

AI treats disciplines as separate because that's how the training data is organized. Mathematics lives in one corpus, biology in another, economics in a third. The model learns the boundaries because the boundaries exist in how humans publish and categorize knowledge. But the most valuable insights often come from synthesizing across these artificial divisions—spotting that a principle from physics applies to market dynamics, or that a biological mechanism explains an economic pattern.

Humans can make these connections because we reason from constraints, not from categories. We ask what depends on what, regardless of which field claims the territory. We spot causal mechanisms hidden in correlation noise because we're looking for why things happen, not just that they happen together. We identify when accepted truths are measurement artifacts or incentive-driven lies because we question foundations, not citations.

And we can predict changes before they appear in the training data because we reason from constraints that haven't broken yet. The corpus shows what happened when constraints bound in the past. Humans predict what happens when different constraints bind in the future.

This isn't just individual edge. It's civilizational progress. When you combine AI's knowledge compression with human constraint reasoning, you don't just get better answers to existing questions. You get new questions that reveal truths previously hidden in the noise. The obesity crisis example shows this. The correlation between grain-heavy diets and metabolic disease was visible in the data for decades. But the question that mattered—what causal mechanism explains this, and what institutional interests kept us from asking—required human reasoning that operated outside the consensus.

Humanity moves to a greater level of understanding when we use machines for synthesis and reserve humans for perspective at the margin. The machine gives us what's known. The human asks what's true. That division of labor is where progress lives now.

Act on Measured Convictions Forged at the Margin

Knowledge and intelligence compress into LLMs. They're abundant, free, instant. Understanding and wisdom remain at the margin. They're scarce, context-dependent, constraint-based. When machines think at expert level, human value moves entirely to marginal thought.

This means reasoning from your constraints, not average constraints. Predicting from your context, not consensus context. Acting on convictions forged by constraint analysis, not corpus synthesis.

Jensen's GPU bet in 1993 wasn't about having more knowledge than everyone else. It was about having a way of thinking when knowledge becomes abundant. Decompose to foundations. Identify constraints. Invert the question. Predict what survives when the foundation breaks. This method produced insight that didn't exist in the corpus. The insight produced conviction. The conviction guided positioning 15 years before the market validated it.

That's the discipline that survives. Not prompting your way to answers, but building the judgment to know which questions matter. Not absorbing consensus, but reasoning from constraints. Not optimizing for today's success, but predicting what survives tomorrow's breaks.

AI gives you execution at scale. It retrieves, synthesizes, and generates at expert level across domains. But understanding doesn't come from retrieval or synthesis. Richard Feynman captured this precisely: "What I cannot create, I do not understand." Understanding requires building the thing from constraints up, seeing why it works, predicting when it breaks. AI can execute the creation. Humans must understand the causation.

This is why prediction matters more than knowledge. Prediction forces you to reveal your causal model. When you predict what happens when a constraint binds, you're stating what you believe causes what. When that prediction fails, you learn where your causal understanding was wrong. When it succeeds, you've validated a piece of constraint logic that becomes transferable intuition.

The age of AI is not a threat to human ingenuity, but a call to elevate it. We are no longer competing on the volume of knowledge we can acquire or the speed at which we can retrieve it. We are competing on the depth of our understanding, the quality of our questions, and the courage of our convictions.

The future doesn't belong to those who can prompt the best answers from AI. It belongs to those who can reason from first principles, spot the constraints before they break, and position for what comes after the break. It belongs to those who can build intuition through deliberate struggle, forge convictions through rigorous falsification, and act with wisdom at the margin.

Method over intelligence. Constraints over corpus. Wisdom over knowledge.

I act on my measured convictions, forged by hindsight with humility, aimed at foresight. The method is replicable. The conviction is personal. The edge is thinking at the margin when knowledge is abundant.

That's the future. Not humans versus machines. Machines for generative knowledge and system-type execution. Humans for causal reasoning, prediction, and building. The machine compresses what's known. The human predicts what breaks and builds what comes next.

Comments ()